Prior to the Covid 19 shut down there

was time to take in some of the many interesting talks

organised for the Chinese New Year by the Trinity Centre

for Asian Studies. First up on 28th January in the Neill

Theatre, Trinity Long Room Hub, was Dr Isabella

Jackson’s talk on ‘A Century of Chinese Children:

‘Little Friends’ in a Changing World.’, the term ‘little

friends’ being a direct translation of the charming

Mandarin word for children ‘ xiao pong yu ‘. Isabella is

Principal Investigator on an Irish Research Council

project ‘CHINACHILD: Slave-girls and the Discovery of

Female Childhood in Twentieth-century China.’ Together

with a team of researchers, she is researching how

controversies over keeping unpaid domestic servants

(binü 婢女 or mui tsai) reflect changing and expanding

conceptions of Chinese childhood.

For all children Chinese New Year is an exciting time.

They can expect to receive new clothes, red ‘hong bao’

envelopes filled with money, as well as enjoying time

off school and consuming plenty of delicious food. They

are also typically doted on by their families as they

are usually the only child and grandchild. However, up

until relatively recently, the notion of childhood as a

time of innocence, when children have the freedom to

learn and develop without the constraints of work

duties, was a privilege reserved almost exclusively for

the offspring of the elite in society … and for boys.

The daughters of the poor were excluded. Instead they

were treated as small women, often sold in the same way

that women could be sold by their families as wives,

concubines, or the aforementioned mui tsai/binü. A

redefinition of the nature and scope of childhood to

include female children was, therefore, a very necessary

one and can only be beneficial for Chinese society into

the future.

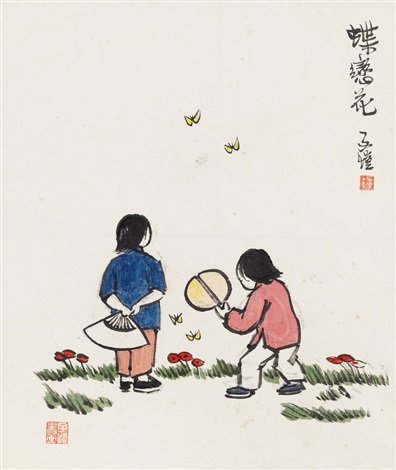

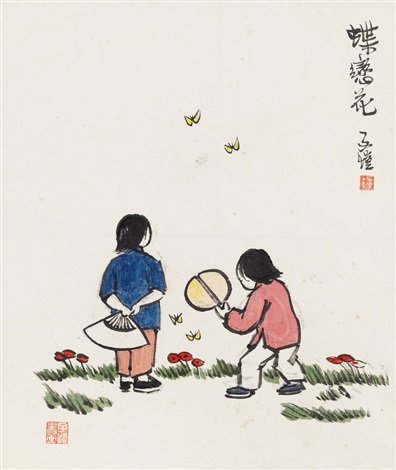

During her talk, Isabella referenced the pioneering work

of the celebrated artist Feng Zikai who had a great

reverence for children and made an important

contribution to this evolving social change in China.

The Shanghai-based artist was to be the subject of

Heather Gray’s talk to the ICCS in March which has had

to be deferred until a time when the society can safely

resume its activities.

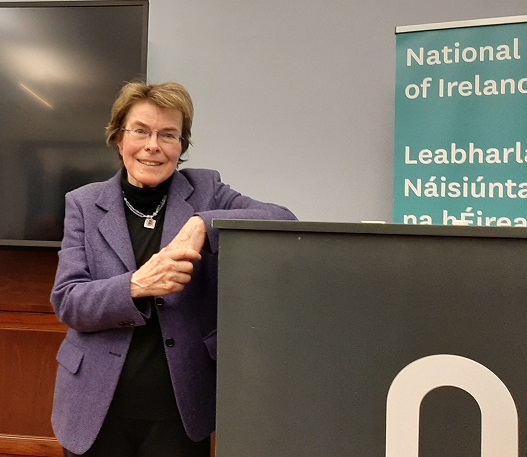

6. 4th February 'Ireland through a

Chinese Mirror.' A talk by Prof. Jerusha Mc Cormack.

Jerusha began by reminding us that you can stand in many

cities around the world and find a Chinese takeaway on

one side of the road with an Irish pub on the other.

Both Ireland and China have an extensive diaspora and

both countries have exported elements of their culture

overseas. In comparing them, of course, there is the

difference in size to take into account. While she was

teaching in Beijing Foreign Studies University one of

her colleagues, on hearing that the population of

Ireland would fit comfortably within the confines of the

city of Harbin, remarked that if it was so small it

could only have small problems. If only that were true!

Despite the differences in scale, there is a parallel

narrative in play in the public life of both countries

as they both espouse a narrative of subjugation by

foreign powers and a sense of victimhood which must be

purged by a resurgence of the national spirit. In this

respect The People’s Republic of China has looked to the

Republic of Ireland for inspiration in the past as we

dealt with the Roman Catholic Church and the British

Empire. Jerusha herself has written about the influence

of Terence MacSwiney on the Chinese poet Guo Moruo and,

on this occasion, she mentioned the Irish writer Ethel

Voynich whose novel ‘The Gadfly’ had the nature of a

true revolutionary as its central theme and sold well

over 2 million copies in China and the U.S.S.R.

Another significant figure mentioned by Jerusha is

Joseph Needham, the eminent British biochemist,

historian and sinologist who has written extensively

about the relationship between Chinese innovation and

strict government control.

In essence, this was another opportunity to benefit from

Jerusha Mc Cormack’s cross-cultural, comparative

scholarship focused on Ireland, the West in general, and

the People’s Republic of China. Along with her

colleague, Professor John Blair, she is engaged in

important intellectual groundwork in supplying us with a

template for improving relations between East and West

by fostering a better understanding of the principles

underpinning our mutual differences.

The Chinese mirror in the title of her talk is no

ordinary mirror. If you look into it and see China from

a purely Western perspective it will reflect back a

defective version of what we conceive society should be

but if you look into it and see China, armed with an

understanding of the mindset and value system

underpinning that society, then you will see the

People’s Republic in its own terms, as it understands

itself to be. This understanding can help us to be less

judgemental and bring the essential characteristics of

our own society into sharper focus as well.

Jerusha’s talks always give pointers to areas it would

be interesting to investigate further. In 1318, the

Irish Franciscan friar and explorer James of Ireland

accompanied Friar Odoric of Pordenone to the Far East,

thus becoming the first Irish person to visit China.

Fast forward to 1924 and we have the initiative known as

The Maynooth Mission to China. This project was

overtaken by the terrible flood in Wuhan in 1931 and the

Columban Sisters working there had to prioritise giving

medical help over the provision of spiritual succour,

‘They came to save souls but ended up saving lives.’

Both of these topics are discussed by Hugh Mc Mahon in

the book of essays edited by Jerusha ‘The Irish and

China Encounters and Exchanges.’This publication by New

Island Books is a welcome addition to the resources

available to those of us who wish to expand our

knowledge of an endlessly fascinating, evolving and

complex field of study.

7. 18th February ‘From Roscommon

to China: Emily de Burgh Daly and Irish Professional

Networks in 19th Century East Asia.’ A talk by Dr.

Loughlin Sweeney. .

A fascinating talk from Loughlin Sweeney of Endicott

College with an intriguing title. Emily French went to

work as a nurse in Ningbo in China in 1888, following

her medical training in London and was to remain in the

country for the next twenty-six years, marrying an Irish

doctor, Charles de Burgh Daly, and raising two children

there. She was the sister of the song writer Percy

French and became an author herself when she published

her memoirs, An Irishwoman in China, in which she

described the customs and people of China, and the

lifestyle of Europeans living there.

We learnt that her husband, Dr. de Burgh Daly, was later

to acquire the distinction of having survived a shot

which was fired at him by Countess Markiewicz during the

1916 Uprising! Emily was one of many Irish professionals

who lived and worked in China in this period, serving

the interests of British informal empire in treaty

ports, customs posts, and commercial concessions.

Dr. Sweeney’s talk gave us an insight into the personal

and occupational networks that tied this distant Irish

community together and explored the motivations which

attracted Irish professionals to China, particularly

their self-identification as empire builders. It is,

perhaps, an aspect of Irish identity that we need to

engage with a bit more. As an instance of this, I had

never heard of Empire Day, the yearly celebration of the

British Empire which was discontinued in 1958 and was

surprised to discover that it was founded by the 12th

Earl of Meath, Reginald Brabazon, whose family seat is

in Killruddery in Bray.

Loughlin’s entertaining article on the Irish Diaspora

Histories Network makes clear the scale of this Irish

involvement in 19th Century China as he imagines the

journey of an Irishman to Shanghai in the 1880s and

introduces us to all the Irishmen in professions as

diverse as doctor to policeman that such a traveller

would have been likely to meet. His research will be

featured in the upcoming book "Imagining Irish Futures",

currently forthcoming from Liverpool University Press.

8. 2020 Autumn Programme.

It is not yet possible to make arrangements

for this year's Autumn Programme. Members will

be informed of developments as soon as possible.

Email: irishchineseculturalsociety@gmail.com

Website: www.ucd.ie/iccs

* * * * * * * * * *