Newspapers focus at least twice as much on broken than on fulfilled promises

Author: Stefan Müller

Date: 6 May 2020

Most voters do not believe that parties deliver on their campaign promises. Previous studies, however, usually conclude that parties indeed keep a large share of their pledges. The media take a crucial role in mediating between parties, politicians, and voters. If citizens receive more information on broken promises, their assessment of government performance might be overly negative and might not correspond to the relatively high degree of campaign pledge fulfilment. Results from a (opens in a new window)new paper, published in Political Communication, show that newspapers exert a strong and consistent negativity bias in reports on pledges. Newspapers report at least twice as much on broken than on fulfilled promises. Moreover, the focus on broken promises has increased in recent years. These findings can help us to understand why voters have such a negative perception of parties’ ability to fulfil their pledges.

“Varadkar pledges tax cuts, pensions hike and public sector pay rises.” Headlines like this one from the Irish Times appear frequently in news outlets before elections. But how do news outlets report on political promises? In a new paper, published in (opens in a new window)Political Communication, I provide the first comparative study of media coverage of pledges throughout 33 electoral cycles. In this assessment of news coverage of election promises, I rely on a novel text corpus consisting of over 430,000 statements on political commitments published between 1979 and 2017 in 22 newspapers from Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.

Coverage Throughout the Electoral Cycle

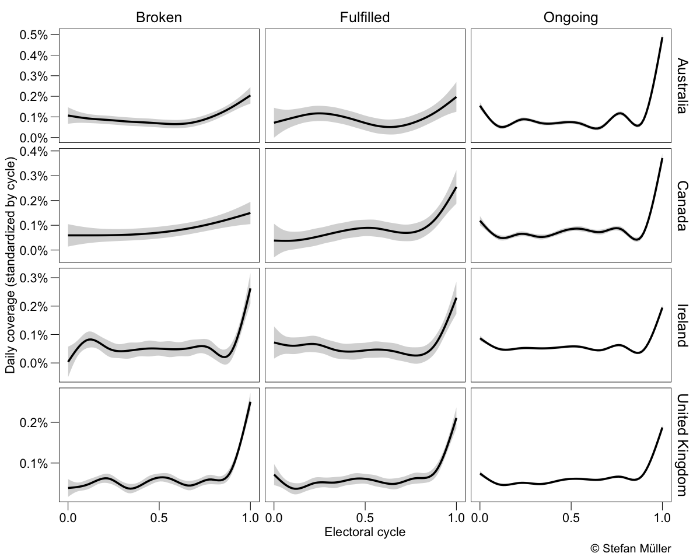

At what times during an election cycle do news outlets focus on political promises? The figure below shows the development of news coverage throughout the 33 electoral cycles. Each electoral cycle (the time between two elections) is standardised from 0 (right after an election) to 1 (right before the next election).

Figure 1: Pledge-related statements throughout the electoral cycle

Coverage of broken, fulfilled, and ongoing promises clearly peak at election time. Statements on ‘ongoing promises’ – political promises that do not contain any information on the breaking or fulfilment – occur most often across all four countries, usually exceeding 90% of news coverage on pledges. Thus, the majority of statements do not contain any statement on the fulfilment or breaking of a pledge, but rather inform about policy proposals or planned policy actions. The results from this analysis are reassuring: the media indeed inform voters about parties’ performances, failures, and policy proposals before elections.

News Outlets Prioritise Broken Promises

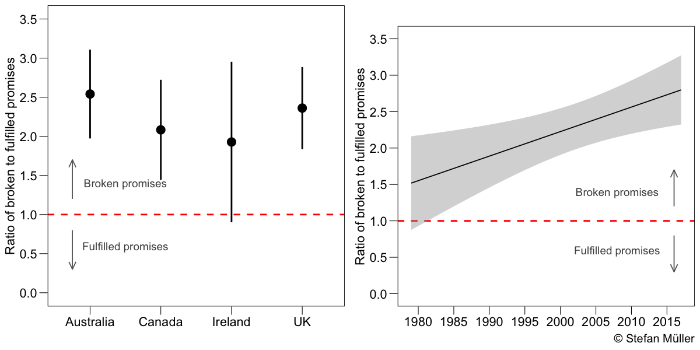

Next, I compare the coverage of broken and fulfilled promises. For each newspaper and quarter, I count the number of statements on broken promises and divide it by the number of mentions of fulfilled pledges. Values exceeding 1 indicate a higher emphasis on broken promises. On average, newspapers across the four countries cover broken promises 2 to 2.5 times more often than fulfilled promises. What is more, the negativity bias in news coverage has increased substantially over time.

Figure 2: The predicted ratio of reports on broken to fulfilled promises

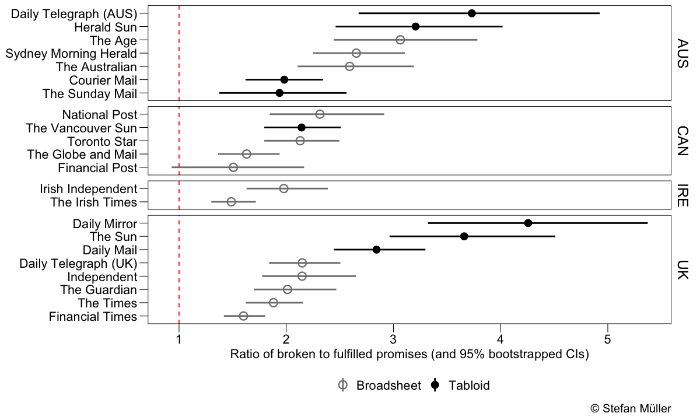

Finally, I analyse substantive differences across newspapers and newspaper types. All 22 outlets focus more on broken than on fulfilled promises. Yet, this negativity bias is stronger in tabloid newspapers, especially in the United Kingdom, a country with high newspaper polarisation. For instance, The Sun and the Daily Mirror focus 3.5 to 4 times more on broken promises.

Figure 3: The quarterly focus on broken promises relative to fulfilled promises

Implications for Democracy

Future research should analyse whether media coverage of campaign promises indeed influences voter perceptions and test whether more salient promises receive more media attention. The results also have implications for parties’ campaign strategies. Given that media coverage is overly negative, parties might need to adjust their campaign communication. For instance, besides extensive party manifestos parties should publish concise booklets that clearly indicate their record in government or opposition and summarise the central pledges. Such documents might be read by more voters than manifestos and provide more direct guidance to assess parties’ achievements and failures.

About the author: (opens in a new window)Stefan Müller is Assistant Professor and Ad Astra Fellow at the School of Politics and International Relations, University College Dublin, and one of the founding members of the Connected_Politics Lab.