Assessment Design

Boud et al (2022) set out some useful guiding principles when approaching assessment in this context:

- Principle 1: Assessment generates learning

- Principle 2: Assessment engages students in active portrayal of their achievements and developing professional identity

- Principle 3: Assessment involves collaboration among the students, academics and industry partners

- Principle 4: Assessment reflects the nature of the actual learning undertaken by individual students during WIL activities

This resource also explores some useful questions to consider in the design process.

At the start of the design of your WIL module’s assessment, it is valuable to consider:

- The wider understanding of assessment (National Forum 2017), which includes not only addresses the assessment of achievement (assessment of learning) but also feedback to students (assessment for learning) and the students ability to evaluate their own learning (assessment as learning).

- Who are the assessors? Given there are three key stakeholders they should all be involved. The more empowered the students are in the process and the more practitioners (employers, industry placement staff) are involved the assessment the more authentic and situated the experience is for students. Practitioners may not always have responsibility, or indeed be allowed to allocate, grades; however, they always have an important role in feedback to students and supporting students to self-evaluate. Research emphasises the importance of inter-stakeholder dialogue when designing and implementing assessment in work-integrated learning. For more on a research study’s findings on how to empower students in assessment on placement, see the video on Empowering Students in the Assessment and Feedback of Work-Integrated Learning Key Stakeholder Views

- What grading scale to use? The learning environment for work-integrated learning can be complex, highly varied and with very different demands and expectation on the learner/students. Therefore, it is not uncommon that there is a reluctance to use highly sensitive grading scales such as percentage or letter grades, as students complain of inconsistency in grading and lack of fairness. This is particularly true in the case where practitioners are assessing in different context. Many professional placements therefore often use a more pass/fail (competent/not yet competent) type of scale. There is often less concern about letter grades/percentages in placements when educators assess through assignments/reports/ presentations. The range of approaches therefore include, for example:

- Pass/Fail

- Distinction/ Pass/ Fail

- Competent /Not Yet Competent

- Bands of Proficiency

- Narrative feedback only

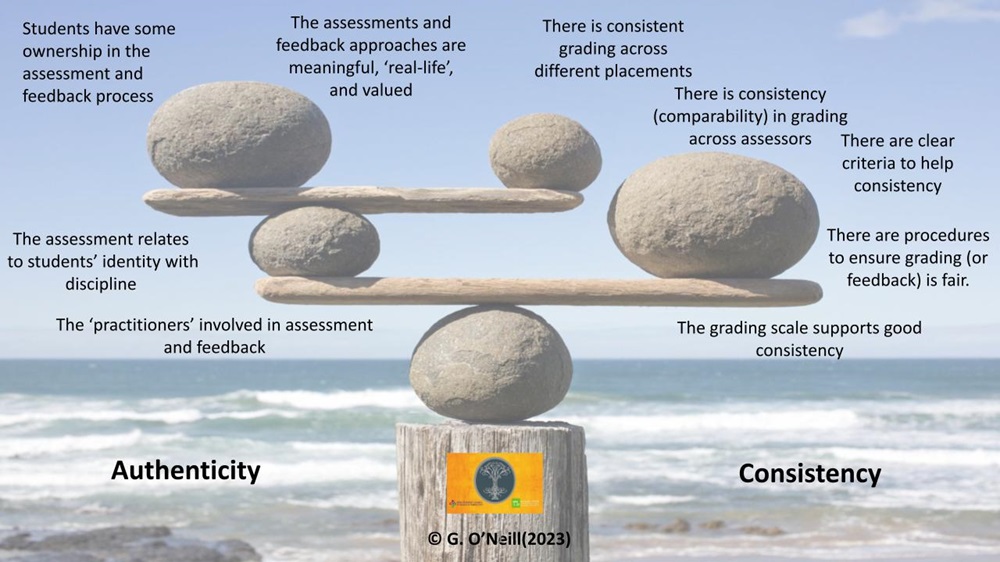

- How do I ensure that assessment is consistent and authentic? Students want assessment to be meaningful and represent what they will be doing when they graduate (authentic assessment). These assessment types can often be complex, flexible, collaborative, vary by context and therefore often different for different students. This can also lead to complaints around consistency. There is a balance therefore in ensuring some consistency in assessment (O’Neill, 2022) and allowing opportunities for different and more authentic learning (Ajjawi et al, 2020).

- Some assessment methods: Depending on the learning outcomes of the placement, consider what are the most appropriate methods.

|

Some common assessment methods that are detailed in our UCD Key Assessment Types include:

(UCD Key Assessment Types, UCD T&L, 2023) |

In addition, the following assessment methods are often used on WIL:

|

Some other key assessment methods that are detailed further in our UCD Key Assessment Types.

Some ideas on different assessment and feedback methods for pre- during and post placement are set out in National Forum (2017b).

References and Resources

- Ajjawi, Rola, Joanna Tai, Tran Le Huu Nghia, David Boud, Liz Johnson & Carol- Joy Patrick (2020) Aligning assessment with the needs of work-integrated learning: the challenges of authentic assessment in a complex context, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45:2, 304-316, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1639613

- Boud, D., Ajjawi, R. & Tai, J. (2020). Assessing work-integrated learning programs: a guide to effective assessment design. Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.12580736

- Ferns, S., & Zegwaard, K.E. (2014). Critical assessment issues in work-integrated learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, Special Issue, 15(3), 179–188ten (2013) Validity in work-based assessment: expanding our horizons Medical Education 2013: 47: 1164–1174 doi:10.1111/medu.12289

- Govaerts, M. & CPM, van der Vleuten (2013) Validity in work-based assessment: expanding our horizons, Medical Education 47: 1164–1174 doi:10.1111/medu.12289

- Jackson, J. Martyn Jones, Wendy Steele & Eddo Coiacetto (2017) How best to assess students taking work placements? An empirical investigation from Australian urban and regional planning, Higher Education Pedagogies, 2:1, 131-150, DOI: 10.1080/23752696.2017.1394167

- National Forum (2017) Expanding our Understanding of Assessment and Feedback in Irish Higher Education . The National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education, teachingandlearning.ie

- National Forum (2017b) Work-Based Assessment OF/FOR/AS Learning: Context, Purposes and Methods. The National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education, teachingandlearning.ie

- O’Neill, G (2022) Assessing work-integrated learning: developing solutions to the challenges of authenticity and consistency, National Forum: Dublin

- Smith, C. (2014). Assessment of student outcomes from work-integrated learning: Validity and reliability. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, Special Issue, 15(3), 209–223.

- Scully, D., O’Leary, M. & Brown, M. (2018). The Learning Portfolio in Higher Education: A Game of Snakes and Ladders. Dublin: Dublin City University, Centre for Assessment Research, Policy & Practice in Education (CARPE) and National Institute for Digital Learning (NIDL)