The urban heat island, heatwaves and climate change

Thursday, 27 November, 2025

Share

Cities are a nexus for many of the issues associated with anthropogenic climate changes. They are home to half of the world’s population and are responsible for more than 70% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Moreover, as most cities are located at low elevations, close to coasts, they are exposed to projected climate changes such as sea-level rise and storms.

At the urban scale, cities also modify the local climate and hydrology profoundly due to the impervious surface cover, built density and emission of waste heat and materials. The result is more frequent flooding, poor air quality and raised air and surface temperatures. This temperature effect is known as the ‘Urban Heat Island’ (UHI) and is a ubiquitous feature of urbanisation. Projected global climate changes, which include more intense rainfall and heatwave events, will enhance these urban effects.

Poor air quality is a feature of many cities. Photo: Photoholgic on Unsplash

Poor air quality is a feature of many cities. Photo: Photoholgic on Unsplash

The UHI has been studied for 200 years, and its causes and controls are well understood. It describes the warmer surface and air temperatures over an urbanised landscape when compared with the natural landscape outside the city. The surface UHI is caused by the extent of paving, the lack of vegetation and the density of construction materials; taken together, these parameters mean that the city evaporates less and warms more than natural surfaces.

The surface UHI is present throughout the day and night and is greatest where the paving is extensive. The air UHI, by contrast, appears at night and is due to the slower cooling of the near-surface atmosphere; its magnitude is greatest about four to six hours after sunset in the most densely built parts of cities. Both the surface and air UHIs are strongest in calm and cloudless conditions, common during anticyclonic weather conditions.

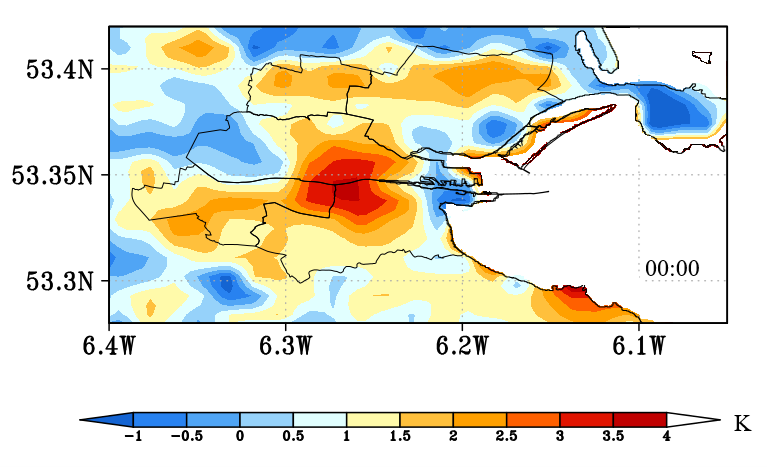

Figure 1 shows the simulated air UHI over Dublin during an exceptionally warm period during May 2018; the values shown are the difference in temperatures when compared to those at Phoenix Park, which represents the natural (background) landscape. Note that warmest air temperatures are found in the densely built parts of the city and Dun Laoghaire.

Figure 1. Dublin’s air temperature UHI during May 2018, which was an exceptionally warm and dry period. The UHI shown is simulated by the Weather Research Forecasting (WRF) model

The UHI can form at any time of the year and in Dublin will raise the wintertime temperature and lower the heating needs of houses and offices. However, in hot weather, the UHI enhances the impact of heatwaves (HW), which represent a global health risk; the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) estimates that 60,000 died in Europe from heat-related exposure in 2022 alone. The weather conditions for HW events are ideally suited to strong UHI formation, such that addressing its causes can help mitigate heat impacts. Traditionally, the response to heat events has been to use air conditioning (AC) that cool indoor air, but this is expensive, and, in many cities, emergency responses rely on providing public access to cool indoor spaces, or climate refuges, during HW events.

However, reliance on AC is not really a viable solution to urban heat stress as the waste heat that they generate contributes to the UHI and outdoor heat stress. Instead, what is needed are nature-based solutions that can mitigate global climate change (i.e., use less energy) and, at the same time, modify the urban landscape to reduce UHI magnitude. This requires changes to urban design and planning to reduce the paved area in cities, strategic planting of tress and the creation of more green spaces. Such changes will help address the urban impacts on temperature, hydrology, and biodiversity.

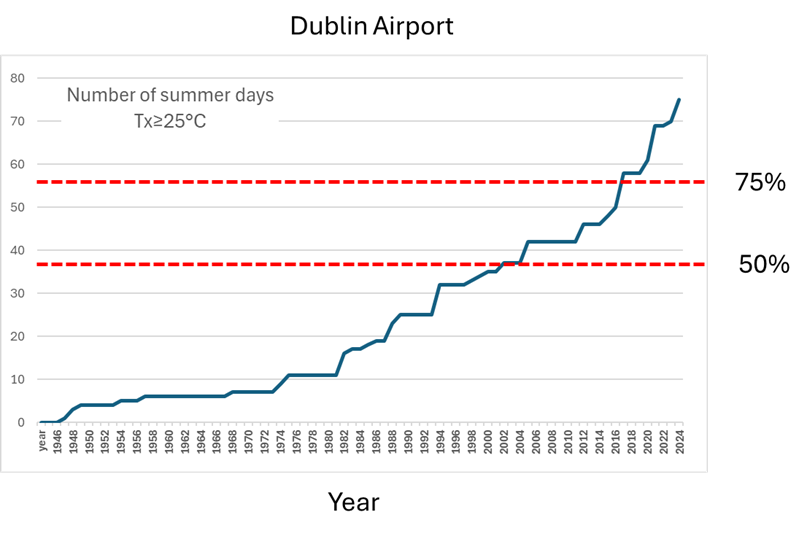

Global climate change projections are clear that the world will get warmer and there is evidence that warming has already occurred. As an example, Figure 2 shows the number of warm days (maximum temperatures over 25°C) recorded during summer at Dublin Airport since the 1940s; note that one-quarter of warm days occurred in the last 10 years.

Figure 2. The number of warm (summer) days with temperatures ≥25°C at Dublin Airport. The counts are presented as a cumulative curve, starting in 1945. Half of the warm days have been recorded since 2000

Compared to other parts of Europe, Ireland does not have a high exposure to extreme heat, but the trend is clear. While the focus in Ireland has been on wintertime heating, we will have to consider building cooling needs in the future. Resilient design would use the UHI as a guide to identify the parts of the city where urban temperature effect is greatest and seek to use landscape management to reduce its magnitude.

About the authors

Professor Gerald Mills is a physical geographer based at UCD who works on the climate of cities. He has served as Secretary and as President of the Geographical Society of Ireland and President of the Irish Meteorological Society. He works with the WMO on Integrated Urban Services initiative which seeks to co-ordinate hydrological and meteorological services at an urban scale and was the recipient of the IAUC’s 2021 Luke Howard Award; an award presented annually to an individual based on lifetime contributions to the development of urban climate science.

Dr Ankur Sati is currently working as a climate research scientist jointly with Dublin City Council and UCD. His work involves generating and researching vital climate indicators that are robust, measurable, and repeatable within the Build CAPACITIES project. He previously worked as a post-doctoral research fellow at UCD School of Geography, focusing on urban CO2 modeling and generating area-based dynamic profiles of emissions and of landscape properties from a diverse set of data within NexSys and Terrain AI projects.