New strategies to treat a deadly childhood cancer

Share

Osteosarcoma, a rare, deadly paediatric bone cancer has defied new approaches to its treatment ever since chemotherapy was introduced in the 1970s. (opens in a new window)Dr Fiona Freeman aims to change that.

“Flares have gone in and out of fashion four times, and yet these patients are still getting chemotherapy. A reason for that is that it is really hard to conduct clinical trials for rare diseases, as it’s hard to get enough patients enrolled,” said Dr Freeman.

In 2023, Dr Freeman was awarded a €1.5 million European Research Council Starting Grant for META-CHIP, a project to develop an organ-on-a-chip approach to study growth of lung metastasis in osteosarcoma.

Explaining what an organ-on-a-chip is, Dr Freeman said, “These are small, microfluidic devices, about the size of an old-school USB key. We’re trying to model bone tissue and how the tumour forms in that.”

In science, a model refers to something that is set up by researchers in the laboratory mimic and study something in nature.

The use of ‘organ-on-a-chip’ devices, she said, offers a way to study disease progression and drug responses without requiring human trials. The devices recreate the environment of a human organ.

“Every organ on a chip is very specific to what organ you are trying to model,” said Dr Freeman. “In our case, we are trying to model bone tissue and how the tumour forms within that.”

The statistics are stark. Osteosarcoma affects one patient per month in Ireland. While rare, it remains a deadly cancer, with no significant treatment advances since chemotherapy was introduced half a century ago, and 90% of drugs are still failing in clinical trials.

After decades, treatment advances are now possible according to Dr Freeman using organ-on-a-chip devices that incorporate all the relevant cell types to better represent how tumours behave in the body.

“It’s not just the cancer cells that are in the tumour micro-environment,” said Dr Freeman. “It’s immune cells, it’s vascular cells, it’s neural cells and these all play a role in how the tumour forms and how the drug might interact with the tumour.”

“My lab is working to create this multi-cellular tumour model, while also incorporating tumour cells directly from patients.”

The organ-on-a-chip approach could help reduce scientists’ reliance on animal testing while also providing more accurate platforms, for testing of new drugs. Pharmaceutical companies have already shown interest in this new approach.

Bone regeneration

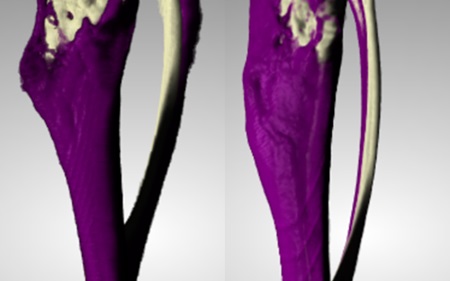

Dr Freeman began her scientific career at (opens in a new window)University of Galway focused on bone tissue engineering. During her doctorate there, she created bone tissue implants that could regenerate large bone defects and she successfully created functioning bone tissue in the lab.

While working in the lab of renowned (opens in a new window)Dr Natalie Artzi at the (opens in a new window)Institute for Medical Engineering and Science in the (opens in a new window)Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Dr Freeman identified a microRNA molecule called mir-29b with the ability to kill cancer cells while also triggering bone to regenerate.

RNA is found in all living cells and, like DNA but with a different structure, it also regulates genes. The molecules that control the types and amounts of proteins that cells make are microRNA.

Dr Freeman’s MIT breakthrough showed how just a single gene could have a dual therapeutic effect by simultaneously destroying cancer cells and promoting bone regeneration. Despite its local therapeutic effect, it was unable to inhibit potentially fatal metastases – cancer cells that have spread from the primary tumour site to other parts of the body. She is now working on therapeutics to complement this breakthrough by targeting metastases.

Early detection

At UCD, Dr Freeman is leading a team of five PhD students and three postdoctoral researchers. The goal of her lab is to discover new therapies by examining the interactions between tumour cells and surrounding tissues in ways never before possible.

One key question that Dr Freeman would like to answer is why symptoms of osteosarcoma typically appear only when the tumour is already large. She aims achieve earlier detection by studying the connections between nerve cells and tumour cells within the bone tissue.

Should Dr Freeman be successful, the impact would extend far beyond Ireland. With 20% of osteosarcoma cases metastasising to the lungs, better understanding of intercellular communications could provide new insights into the progression of this cancer.

The research, which is supported by funding from the European Research Council, Research Ireland and Sarcoma of America, is still in its early stages. The most immediate goal is to reach pre-clinical trials and develop new spin-out technologies.

Dr Freeman is also developing exciting new nanoparticle-based therapies to transform the environment in which a tumour operates in from so-called ‘immune cold’ that repels immune cells to ‘immune hot’ where immune cells can target the cancer.

Meanwhile, Dr Freeman is helping to establish a new UCD Cancer Centre, in collaboration with clinicians from (opens in a new window)St Vincent’s and St James’s hospitals. This is part of her mission to bridge the gap between laboratory experimentation into clinical application.