UCD astronomers prove decades old theory on how young stars grow

Posted 26 August, 2020

Researchers at University College Dublin have confirmed for the first time a 30-year-old theory explaining how stars are formed.

New observations by an international team led by scientists from the UCD School of Physics, (opens in a new window)Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS), and the (opens in a new window)Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany proved that the magnetic field produced by young stars are a key element to their growth.

(opens in a new window)Writing in Nature, lead author Dr Rebeca García López, an Ad Astra Fellow at UCD, explained how the researchers were able to capture the process in which stars effectively suck in gas and dust orbiting around them, dragging the stellar matter down onto their surfaces.

“Previously scientists suspected that new stars and planets were born from matter surrounding existing stars through a process called magnetospheric accretion,” she told the (opens in a new window)Irish Independent.

"However, this was not confirmed until we carried out our ground-breaking study and saw first-hand the process in action.

"We were able to see how matter from its surrounding disc is channelled on to the star, enabling it to gain weight.

“This makes us the first researchers to confirm the process by which new stars - and, ultimately, planets - are born," she added.

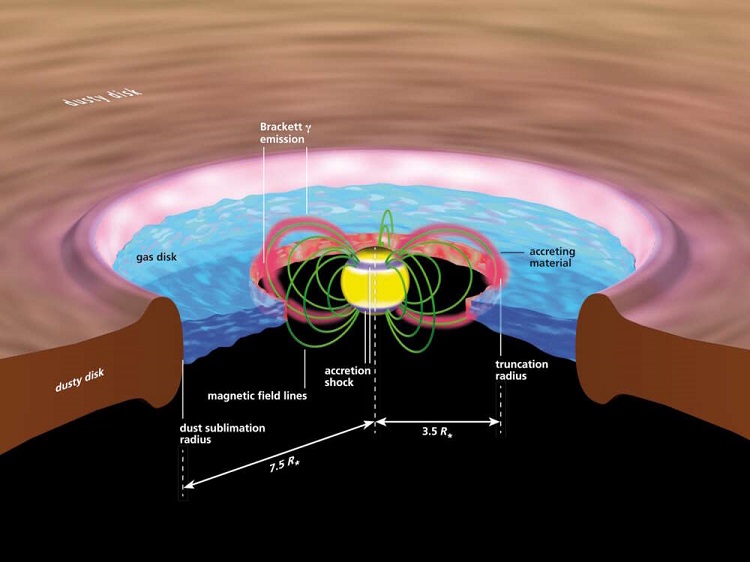

A representation of the process by which young stars use their magnetic fields to channel gas and dust onto their surface. Image: MPIA graphics department

How stars are formed has long been speculated; what is known is that they come from giant molecular clouds of gas and dust which collapse into a dense ball of matter made mostly of hydrogen.

This collapse creates the right condition for the core of the star to initiate nuclear fusion, causing it to spin. While this rotation is important, its spin makes it more difficult for the material to reach the star.

Thirty years ago astrophysicist Max Camenzind proposed a solution to this problem, that the magnetic fields of young stars helped shed momentum in such a way that it allowed gas and dust to flow onto the star.

Dr García López and the rest of the international team spent 18 months studying this behaviour using the world's most powerful telescope based at the European Southern Observatory up in the Andes Mountains in Chile.

GRAVITY, which combines four 8-meter VLT telescopes, allowed the researchers to observe the inner part of the gas disk surrounding TW Hydrae - the nearest star to our own, and the youngest at less than ten million years old.

“This star is special because it is very close to Earth at only 196 light-years away, and the disk of matter surrounding the star is directly facing us,” said Dr García López.

“This makes it an ideal candidate to probe how matter from a planet-forming disk is channelled on to the stellar surface.”

The team plans to continue monitoring to TW Hydra, hoping to understand if and how the magnetic field changes, and whether it experiences a North Pole/South Pole dynamic or something more complex.

By: David Kearns, Digital Journalist / Media Officer, UCD University Relations