Opinion: How sex work has been affected by the pandemic

Posted 13 May, 2021

Challenging circumstances. (opens in a new window)Vlue

Challenging circumstances. (opens in a new window)Vlue

In the months before the pandemic, I was involved in an (opens in a new window)extensive piece of research into the sex work industry in the UK. Focusing on the main online market for sex work in the UK, (opens in a new window)AdultWork, we analysed the profiles of more than 11,500 sex workers to understand the industry and how it operates online.

The total number of sex workers in the UK (opens in a new window)was estimated in 2016 to be slightly over 70,000, so our sample was a substantial portion of the industry (albeit not necessarily a representative sample). The findings, and follow-up work that I have done subsequently, give some valuable insight into the shape of the sex industry in the UK, as well as some of the changes and challenges experienced by sex workers during the pandemic.

One of the main findings from our study, which was (opens in a new window)recently published in the Journal of Culture, Health & Sexuality, was that more than half of the female sex workers in our cohort were not British. The majority of these non-British workers identified as being from eastern European countries (the next largest was western Europeans, including Spaniards and Germans, but it was a far smaller proportion). Many travelled to the UK for a few weeks of work followed by a return to their home country, where they had family and dependants to feed. Sex work was their main source of income.

We found that eastern European sex workers in the UK charge 30% less than their British colleagues, despite their profiles being viewed by more people on average. The reason for the lower charges (opens in a new window)has been argued to be because they feel less secure about their job, and because they need a minimum income to cover the cost of hotels, flights and so on and can’t risk ending up with too little.

These workers were often the ones who provided riskier services, such as unprotected sex or extreme BDSM (bondage, dominance and submission/sadomasochism). In many ways, they are also probably the workers who have been most challenged by the pandemic.

Sex work and the pandemic

We have heard a lot about how the pandemic has been very difficult for industries that bring people together such as pubs, restaurants and airlines. Sex work has also been severely challenged by the fact that people have not been allowed to physically interact outside their households in the UK and elsewhere during most of the pandemic.

Unlike most other industries, many sex workers (opens in a new window)have not been eligible for government support during the crisis. Because many (opens in a new window)do not have records of their taxed income they have been unable to benefit from the UK (opens in a new window)income support scheme for self-employed people. This is even more likely to have been the case for the many sex workers in the UK whose primary residence is abroad.

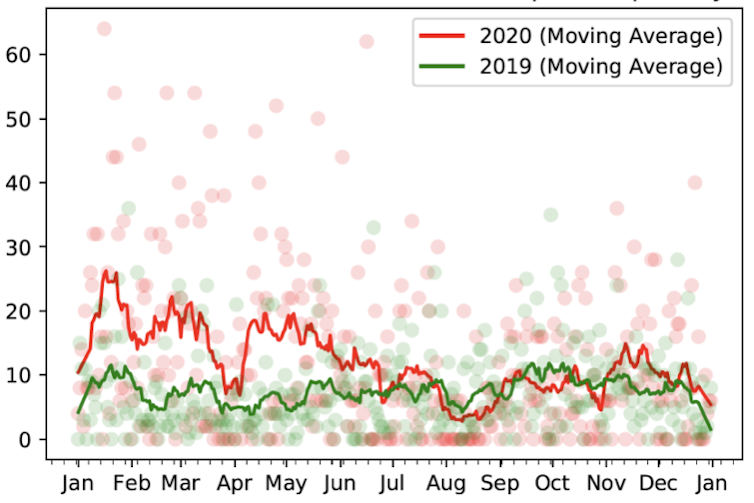

Factors such as clients’ health concerns and limited mobility have (opens in a new window)reduced demand for sexual services during the pandemic. (opens in a new window)Reports have also noted that many sex workers turned to offering online services. Yet that does not mean that no in-person sex work has been taking place, as we found during follow-up research. Though it is very difficult to produce comprehensive statistics on the volume of sexual transactions, a simple comparison between the daily number of reviews that clients left on AdultWork after receiving services in 2019 and 2020 suggests there has been no substantial decline in the number of encounters – see the graph below.

AdultWork reviews per day, 2020 vs 2019

Taha Yasseri

Taha Yasseri

Sex work is one of those jobs that has never stopped being demanded and supplied, (opens in a new window)neither during wars nor famines, so it would be naïve to think otherwise in the case of a pandemic. In fact, the pandemic-induced financial pressure (opens in a new window)has reportedly made former sex workers return to the sector and many newcomers (opens in a new window)start working in the profession too.

If the level of business has stayed fairly constant in a market in which the supply has potentially gone up, it means that sex work has become more competitive during the pandemic – and even more so for vulnerable workers at the “low end” of the market. A more competitive market is likely to mean that workers either lower their prices or take bigger risks with the services they provide, or both at the same time. My preliminary analysis shows that the gap between the highest and lowest prices has increased during the pandemic.

On top of that, when meeting people outside of your household is illegal, in-person sex work effectively becomes illegal too ((opens in a new window)in the UK sex work is normally legal, though various activities, including pimping, running a brothel and soliciting in a public place, are all illegal). This (opens in a new window)is likely to have meant that vulnerable workers have been taking bigger risks while being afraid of the legal consequences of, for example, going to the police to report an assault by a client.

COVID vaccines for sex workers

Many countries have been prioritising COVID vaccinations based on people’s age, type of job, and pre-existing health conditions. In (opens in a new window)our analysis, we found out that the majority of sex workers, as well as ones most in demand, were aged between 18 and 36, which puts them at the end of the queue for vaccines.

This would only change if governments recognised that sex work has not stopped in spite of the social-distancing restrictions, and considered the health risks that sex workers take in their day-to-day jobs and the benefits of an early vaccination both for them and society as a whole. At a time when sex workers’ usual access to healthcare support such as GPs and sexual-health nurses (opens in a new window)has been disrupted, this is something that governments should look into urgently.

By (opens in a new window)Taha Yasseri, Associate Professor, School of Sociology; Geary Fellow, Geary Institute for Public Policy, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

This article is republished from (opens in a new window)The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the (opens in a new window)original article.

![]()