Ancient cattle bones offer new insights into the construction of Ireland's megalithic marvels

Posted 31 January 2023

Megalithic construction in Ireland could have been fuelled by the adoption of draught animals in the 4th Millennium BC, (opens in a new window)according to new research based on cattle remains found at an archaeological site in Dublin.

Data collected from the M2 motorway Kilshane excavation in 2004 and further analysed by researchers from the UCD School of Archaeology strongly suggests the exploitation of animal labour in the Middle Neolithic period in Ireland.

The findings of Dr Fabienne Pigière and (opens in a new window)Associate Professor Jessica Smyth argue that cattle in Neolithic Ireland were used not only for their meat and their milk but also for their strength; that access to draught animals, and the exploitation of associated resources, were at the heart of wider changes that took place in Neolithic Ireland at the time.

Animal traction likely assisted a range of contemporary activities from forest clearance to ploughing, as well as the transportation of large stones and bulk loads of timber and manure.

Its adoption provides a key support for more extensive practices as well such as megalithic construction, which increased considerably in scale during this period.

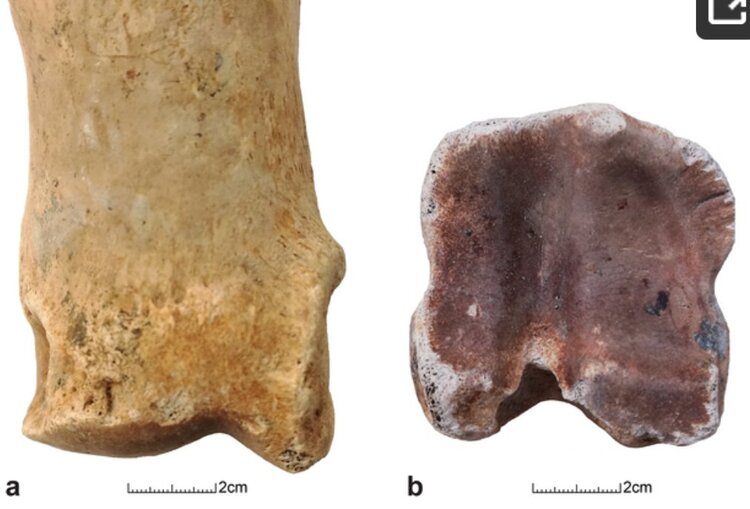

“Detecting the traces of traction on prehistoric animal bone is not straightforward at all - we compared the Kilshane data with bone pathologies from modern draught animals and wild animals never used for traction. Only then were we confident about what we found,” said Dr Fabienne Pigière.

The earliest passage tomb activity recorded in Ireland, to date, is at Carrowmore, County Sligo and Baltinglass, County Wicklow, around 3,700 BC, with the Baltinglass tomb at an altitude of nearly 400 metres above sea level.

The more ‘developed’ passage tombs such as Newgrange, dated 3300-3000 BC, found in the Boyne Valley incorporate kerbstones, orthostats and other stone elements sourced from long distances, up to 75 km in the case of quartz and granite used at the World Heritage Site.

Based on the evidence found at Kilshane, it is likely cattle traction was used and even enabled the transport of both large and small stones over long distances and to higher terrain, as well as considerably easing efforts at a more local scale.

Once on site, manoeuvring large structural stones into position would also have been easier with animal traction.

“To find this evidence on the Kilshane cattle bone is so exciting. It really makes us think in new ways about social organisation and early farming in Ireland at this time,” said Associate Professor Jessica Smyth, who led the research as part of the Irish Research Council's Laureate scheme.

The absence of evidence for cattle (and oxen) traction in the Irish Neolithic has previously created a reluctance to speculate on the construction methods of Ireland’s passage tombs and megalithic monuments.

Prehistoric bone assemblages were generally poorly preserved in Ireland until the discovery of the bone assemblage enclosure at Kilshane, north county Dublin.

The remains of at least 58 individual cattle recovered from its ditches - dating back some 5,500 years - represents an exceptionally important 'window' on Neolithic animal husbandry in Ireland and the UK.

Evidence at the site show that at least some of the cattle deposited at Kilshane had been used for traction, as pathologies on these individuals’ bones showed a distribution pattern similar to draught cattle used today.

By: David Kearns, Digital Journalist / Media Officer, UCD University Relations

To contact the UCD News & Content Team, email: newsdesk@ucd.ie