Oireachtas committee hears assisted dying has no overall impact on reducing suicide rates

Posted 8 November 2023

An Oireachtas committee has heard assisted dying has no overall impact on reducing suicide rates.

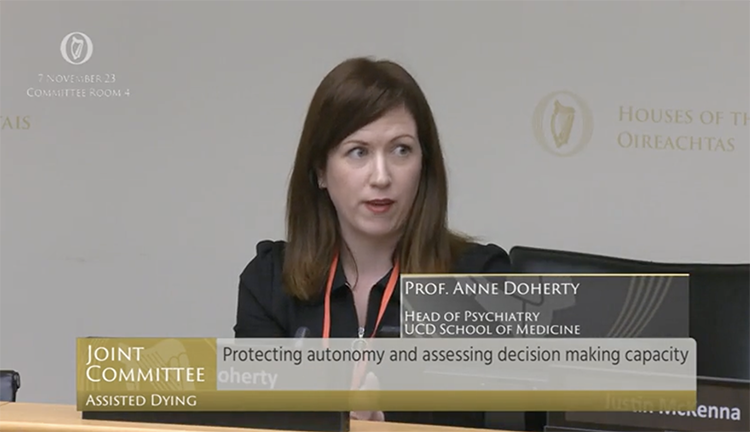

(opens in a new window)Associate Professor Anne Doherty told the Joint Committee on Assisted Dying that a systematic review examining the often made argument that assisted dying reduces suicide rates had found “suicide rates did not significantly change” in countries that had introduced any form of assisted dying.

“We found… there was no overall reduction in self-initiated deaths, and that overall, suicide rates did not significantly change,” said the consultant liaison psychiatrist at the Mater Hospital and academic at the UCD School of Medicine.

The (opens in a new window)Joint Committee on Assisted Dying was established to consider and make recommendations for legislative and policy change related to a statutory right to assist a person to end their life and a statutory right to receive such assistance.

A medical expert in the specialty of integrated care for people with mental and physical health problems, Associate Professor Doherty is a local Clinical Lead for Self-Harm and Suicide-related ideation, and provides mental health care to people with cancer as part of the Psycho-Oncology Service of the National Cancer Control Programme.

In her evidence to the committee she expressed concerns about people with treatable mental illness accessing voluntary assisted dying.

“We identified that in Oregon and Switzerland the research reported a significant increase in older women seeking assisted dying and dying by suicide, and this is concerning because older women have high rates of depression.

“This trend raised the question of whether these deaths were being driven by potentially treatable depressive illnesses being left untreated, and whether there is a gendered impact influencing this."

She noted that the premise of many assisted dying laws in other countries such as Queensland, Australia were founded on the basis that a person “is experiencing intolerable suffering which cannot be relieved”.

“Can mental distress be as severe as physical symptoms in terms of quality of life? Absolutely yes, and this is why in Canada a court challenge has resulted in a change in the law to allow people to access assisted suicide on grounds of mental illness alone.”

Adding: “People can have a significant depression, with symptoms which include low mood, hopelessness, negativity towards the future and a wish to die, without necessarily lacking capacity.

“However, in such a case the person’s low mood will certainly affect how they think and how they experience emotion. It’s hard to know how we would robustly ensure that a person in this situation would receive mental health treatment if they had an entitlement under the law to assisted dying. As well as mental health conditions and cognitive conditions, there are a range of psychosocial factors which might impact on decision-making such as coercion and elder abuse,” she added.

Ireland has had notable success in reducing suicide rates in the past decade, Associate Professor Doherty said, but that there remains stigma towards mental health challenges.

Mental healthcare in Ireland receives around 6% of the health budget compared to 12-13% in other comparable countries, something she told the committee needed to be addressed to ensure that people are “providing the highest standard possible of health care both mental and physical and that [they] have full access to adequate palliative care and mental healthcare.”

“It would be a travesty if assisted dying became a substitute for assistance in living.”

By: David Kearns, Digital Journalist / Media Officer, UCD University Relations

To contact the UCD News & Content Team, email: newsdesk@ucd.ie

UCD academics on The Conversation

- Opinion: The leap year is February 29, not December 32 due to a Roman calendar quirk – and fastidious medieval monks

- Opinion: Nigeria’s ban on alcohol sold in small sachets will help tackle underage drinking

- Opinion: Nostalgia in politics - Pan-European study sheds light on how (and why) parties appeal to the past in their election campaigns