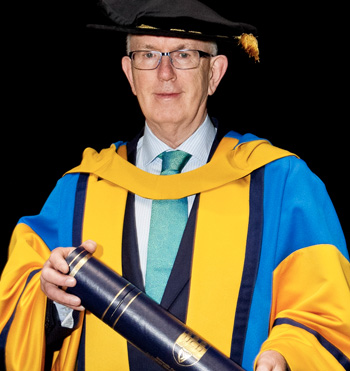

Barry O'Leary

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN

HONORARY CONFERRING

Thursday, 4 December 2014 at 5 p.m.

TEXT OF THE INTRODUCTORY ADDRESS DELIVERED BY PROFESSOR DONNCHA KAVANAGH on 4 December 2014, on the occasion of the conferring of the Degree of Doctor of Laws, honoris causa on Barry O’Leary

President, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen

It’s an honour and a pleasure to introduce Barry O’Leary, who has recently retired as CEO of IDA Ireland after a long career of public service with the IDA. We welcome not only Barry, but also his wife Máiréad and his son Barry, and we also say hello to his other son Ciarán who is in the US at the moment.

It’s an honour and a pleasure to introduce Barry O’Leary, who has recently retired as CEO of IDA Ireland after a long career of public service with the IDA. We welcome not only Barry, but also his wife Máiréad and his son Barry, and we also say hello to his other son Ciarán who is in the US at the moment.

When we honour people with honorary degrees we also signal what we value as a university and as a business school. In that context, I would like to stress three themes.

First, the success of the IDA, which by any measure has been spectactular, and the role that FDI plays in the Irish economy;

Second, Barry's quiet and effective approach to such things. No drama is one of his qualities in a world that can be dramatic;

Third, the importance of public service to us and to our students. The value of public service and servant leaders can often be lost in a short-term, instrumental focus. However as a School we signal our support for true servants of the public and servant leaders such as Barry.

We also gave Frank Ryan, former CEO of Enterprise Ireland, an honorary degree this time last year and will therefore have consciously honoured both agencies of economic growth. We were waiting until Barry had stepped down to mark his contribution.

The Industrial Development Authority was set up by the state in 1949, and it started with a staff of 11. As a small agency, it wasn’t particularly active during the 1950s and 1960s when the focus of the economy was on agriculture. However, the fifties was an important period of institution building when the government set up a whole constellation of research and development agencies focused on the land, the public sector, the private sector, the economy, the built environment and industry.

It wasn’t particularly active during the 1960s either, though the introduction of free education at that time proved to be a hugely important initiative and a foundation for its subsequent success. In 1969, it merged with An Foras Tionscail and became a semi-autonomous agency. By 1971 it had a staff of 237. Today it has a staff of 270 which is a remarkably small number given that it has offices in 19 locations outside of Ireland and 9 offices in Ireland.

In 1970s, the new agency focused on attracting the manufacturing function of international companies to Ireland. In line with this strategy, the state invested in training and vocational education, setting up the Institutes of Technology at that time. Barry joined the IDA in 1976, having held a number of different positions in industrial companies including Nestle and the Smurfit Group.

During the 1980s, the IDA began to move into the life sciences and software, as Ireland’s dalliance with heavy industry — e.g. Fords and Dunlops in Cork—made it clear that we’d have to attract industries producing products with a high value to weight ratio. Perhaps fortuitously, Ireland never really experienced Fordism, and was, even in the 1980s, creating, through the IDA, important pieces of the jig-saw that would become known as post-Fordism.

Other significant developments during the 1980s included the creation of the IFSC here in Dublin and the introduction of the 12.5% corporate tax rate.

Thinking of the 1980s, reminds me of a very popular satirical show, Yes Minister, which lampooned politicians and bureaucrats, and perhaps most memorably through its depiction of the bureaucrat, Sir Humphrey. Some of you will know this character from re-runs, and the caricature spoke to a general cynicism of the time towards state bureaucracy. However, to my mind those working with the IDA were the very antithesis of Sir Humphrey, and indeed the IDA was in the van of an Irish initiative that reimagined the role of the state in industrial development. Barry was very much part of that endeavour, working for the IDA in German between 1983 and 1991.

The government restructured and refocused the IDA during the 1990s, creating Enterprise Ireland to focus on developing indigenous industry while the IDA focused on attracting foreign direct investment to Ireland. Hence the numbers employed by the IDA dropped from 545 in 1993 to 280 in 1998. Its strategy was to focus on small but promising companies, mainly in the US and it was tremendously successful at its job. One measure of its success is that U.S. firms invested more capital in Ireland between 1990 and 2011 than it did in the four BRIC nations combined.

Barry returned to Germany in 1995 where he was responsible for running the IDA’s offices in Stuttgart and Düsseldorf, which covered Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Italy. He subsequently became Director of Europe and centralised IDA’s German offices into Frankfurt. During this period he was closely associated with winning major projects from companies such as Bertelsmann, SAP, Deutsche Bank, Lufthansa, Kostal, Allianz and a number of key Italian financial services institutions.

In the new century, the IDA shifted its focus to high-end manufacturing, R&D and innovation. Barry returned to Ireland in 2002 and was initially appointed Divisional Manager Pharmaceuticals and Biopharmaceuticals and a member of the IDA’s Executive Committee. His responsibilities were increased in 2004 to include the Life Sciences and Information and Communications Technology areas.

He led IDA teams in winning significant investments from a number of key clients such as Lilly, Pfizer, Centocor, Boston Scientific, Cordis, IBM, Kelloggs, Merck, Citi, Cisco Systems and Facebook among others.

In 2008, he was appointed CEO of the IDA at a time when there was significant economic turmoil and challenges, not least to Ireland’s reputation. The IDA has responded superbly to these challenges and under his leadership the team delivered record levels of inward investment for Ireland. Today, more than 265,000 people are employed either directly or indirectly in IDA supported companies. More locally, Barry was a key driver of the development of the National Institute for Bioprocessing Research and Training, a global centre of excellence for training and research in bioprocessing, which is located on the UCD campus.

Barry has also been the dominant figure in mapping out a new strategy for the IDA, one that is focused on the various elements that go to make up what is known as the ‘smart economy’. That strategy is also centred on clean technologies and has also shifted the organisation’s international marketing effort towards emerging market, with new offices opening in Mumbai, Boston, Orange County, Moscow and Sao Paulo. Domestically, the strategy seeks to have 50% of investments outside of Dublin and Cork. It is also worth highlighted that the IDA is not solely about attracting FDI to Ireland but it also plays a central role in driving organisational change and transformation within its client companies. A good case of this is IBM, which at one time had 3500 people employed in manufacturing here in Ireland. Today it has nobody in manufacturing, but it has 4000 employees here.

Looking back on the history of the IDA, and contrary to popular understandings of the state’s proper role in the economy, it is clear that high tech growth in Ireland has been promoted by a new form of state intervention in the economy—one that fosters local networks of support through decentralized state institutions drawing on extensive local, national and global resources.

The strapline that the IDA has used in its recent advertisements is that Ireland is a place where ‘innovation comes naturally’. Whatever about Ireland, I think any review of the IDA will conclude that it certainly is an organization where ‘innovation comes naturally’.

Tréaslaím leatsa, a Bharry, as an onóir atáimid chun bhronnadh ort anois, as an sár-obair a dhein tú agus do bhaill tríd na blianta, ar mo shon, ar son an comhluadar atá anseo, agus ar son muintir na hEireann. Go n-eirí leat agus go raibh míle míle maith agat.

Praehonorabilis Praeses, totaque Universitas,

Praesento vobis hunc meum filium, quem scio tam moribus quam doctrina habilem et idoneum esse qui admittatur, honoris causa, ad gradum Doctoratus in utroque Jure, tam Civili quam Canonico; idque tibi fide mea testor ac spondeo, totique Academiae.