“What brought you to Dublin?”

By Hiroaki Imoto

November 2025

Many people have asked me this question, and I often say it’s because I fell in love with Guinness. But the truth is, there’s a bit more to the story.

The beginning of my systems biology journey

Soon after entering university, I realized that biology wasn’t my favorite subject. I often found myself sneaking out of biology classes to attend lectures in the physics department—especially those on thermodynamics. It wasn’t because I believed physics would help me understand biology better; I was simply curious and found it fun (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Throwback to my thermodynamics report.

In my final undergraduate year, I had to choose a laboratory to join. Around that time, Prof. Mariko Okada had just moved from RIKEN to Osaka University, and that’s when I first came across the term “systems biology.” I was immediately fascinated—particularly by the idea of mathematical modeling of biochemical reaction networks.

My first task in the Okada lab was to reproduce results from several established models1,2. These pioneering works inspired me deeply and laid the foundation for my PhD research. I wanted to know whether model prediction accuracy could be improved by incorporating cell line– or patient-specific characteristics, such as transcriptomic data, into generic kinetic models. My doctoral thesis focused on mechanistic dynamic modeling to better stratify breast cancer patients and showed that personalized kinetic models could identify potential drug targets3.

A new direction

After my PhD, I wanted to take this further: if kinetic models can identify drug targets, could we also model protein–drug interactions to find effective ways to inhibit dysregulated signaling pathways?

At that point, I hadn’t planned to go abroad—Japan is, after all, a comfortable place for Japanese people. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and I began to think more seriously about my future. Mariko encouraged me, saying, “JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) provides travel fellowships for PhD students. Hiroaki, you should apply and learn systems biology from Boris.” I was fortunate to receive the JSPS Overseas Challenge Program for Young Researchers, and I remain deeply grateful for her encouragement to step out into a new world.

So, during the pandemic, I flew to Ireland (Figure 2), forgetting my fears of different cultures and languages.

Figure 2: A quiet, deserted Kansai International Airport — my first step toward Ireland during COVID.

Joining SBI

I spent six months at the Systems Biology Ireland (SBI) as a visiting student, learning how to build models that include detailed protein–protein and protein–drug interactions. To achieve this, we needed to incorporate thermodynamic factors4, something that brought me right back to those thermodynamics lectures I had enjoyed as an undergraduate. Sometimes the dots connect in the most unexpected ways.

I loved the stimulating discussions at SBI and felt strongly that I wanted to continue working in the Kholodenko–Rukhlenko group. Thanks to the JSPS Overseas Research Fellowship, I was able to return to SBI as a postdoctoral researcher.

Our recent work

In our recent study published in Cell Reports (2024)5, we investigated three pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cell lines with different KRAS mutations. These cell lines respond differently to kinase inhibitors, and we hypothesized that cell line–specific models could help reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying drug resistance—and suggest strategies to overcome it.

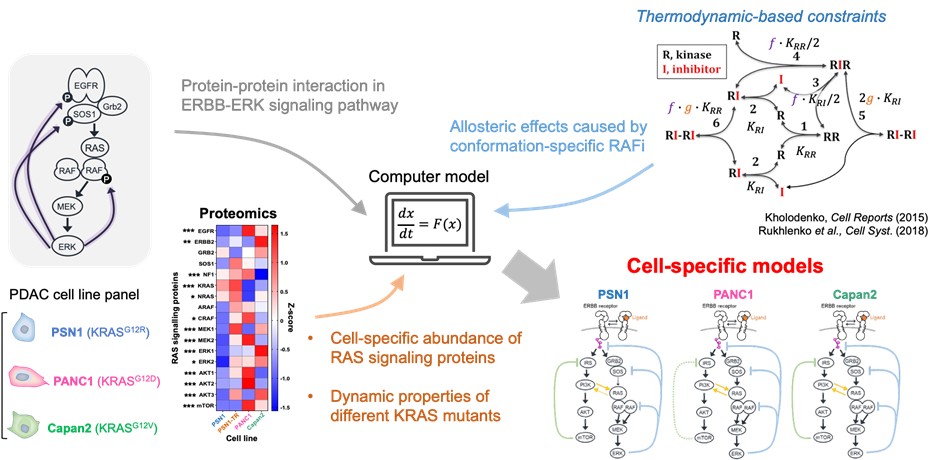

During my PhD, I learned how to make models context-specific. As a postdoc, I learned how to incorporate structural and thermodynamic properties into kinetic models. Now it was time to combine both approaches! We built PDAC cell line–specific models that integrate proteomic data and the dynamic properties of different KRAS mutants (Figure 3). Then we asked the model a simple question: “What causes resistance to RAF inhibitors?”

Figure 3: From generic model to cell-specific models.

The model predicted that resistance was driven by ERBB receptor—and that inhibiting ERBB could sensitize cells to RAF inhibitors. We tested this experimentally, and indeed, in RAF inhibitor–resistant cell lines, ERBB inhibition sensitized cells to Type II RAF inhibitors—in excellent agreement with model predictions (Figure 4).

In fact, our work goes even further — it reveals a way to effectively inhibit oncogenic ERK signaling regardless of the KRAS mutant context. Please have a look 👉 (opens in a new window)https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114710.

Figure 4: Cell line specific models predict the mechanism of drug resistance to RAF inhibitor.

Adapted from Sevrin et al., Cell Reports (2024), DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114710.

This study demonstrates that computational models individualized to specific cell lines are useful and powerful tools to identify mechanisms of drug resistance and strategies to overcome it.

Coming back to the question in the title, my passion for systems biology has brought me this far. Looking ahead, I hope to continue this journey—ultimately toward building a digital twin for designing personalized therapies.

References:

- Kholodenko, B. N., Demin, O. V, Moehren, G. & Hoek, J. B. Quantification of short term signaling by the epidermal growth factor receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 274, 30169–30181 (1999).

- Nakakuki, T. et al. Ligand-specific c-Fos expression emerges from the spatiotemporal control of ErbB network dynamics. Cell 141, 884–896 (2010).

- Imoto, H., Yamashiro, S. & Okada, M. A text-based computational framework for patient -specific modeling for classification of cancers. iScience 25, 103944 (2022).

- Kholodenko, B. N. Drug Resistance Resulting from Kinase Dimerization Is Rationalized by Thermodynamic Factors Describing Allosteric Inhibitor Effects. Cell Rep 12, 1939–1949 (2015).

- Sevrin, T. et al. Cell-specific models reveal conformation-specific RAF inhibitor combinations that synergistically inhibit ERK signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Rep 43, (2024).