Notes on a Pandemic from a Clinician Scientist

A little over a year ago I was anxiously awaiting the start of my medical career. After 12 years of university, my husband was anxiously awaiting the arrival of my first paycheck. I have a love affair with science that began when I found my dad’s old chemistry set as a child. Back when there weren’t as many regulations (or any for that matter) on what was safe to be included in a child’s toy and things blowing up was the epitome of an experiment that worked. As chemical compounds became more complex and blowing things up became a thing of the past, I slowly switched my allegiance to genetics completing a BA in Human Genetics, followed by a PhD in Translational Medicine focussed on immunology, thoracic oncology and epigenetics.

Now that the hardships of the PhD have been blurred with nostalgia, I’m so glad that I took a long and winding route to get here. My PhD was an experiment in collaboration that encompassed scientists, doctors and even non-scientists successfully. It taught me the importance of a multidisciplinary approach and how the “bench to bedside” approach could be enhanced when you were involved in every step of that process. And as it progressed, I knew that I wanted to be more than a facilitator, I wanted to be a bridge between the two disciplines, to follow in the footsteps of the amazing clinician scientists I met along the way.

Fast forward four years and I was about to start my intern year. And in “grass is always greener” fashion, I was undertaking an academic internship where I would spend nine months in clinical rotations followed by a three-month research rotation. When preparing to start my clinical training last year I was terrified. In research, making a mistake would cost you time, money, and sanity. But apart from your frustrated supervisor, no-one else would be affected. In medicine, a mistake can cost someone their life. A month before, I was learning how to be a doctor, now I was a doctor, having somehow bypassed the part with training wheels. It was terrifying. It was brilliant. It was at times boring and monotonous and I felt like all I was doing was paperwork. As the year went on I couldn’t wait to start my academic rotation, which would combine my interest in paediatrics and haematology/oncology into research that I hoped would benefit future patients. And then, all of a sudden, we were in the middle of a pandemic.

During my undergrad I had a series of lectures by Professor Luke O’Neill, an immunologist in Trinity. His lectures were always witty and enjoyable; you learned a lot, and some things he said would stick with you. In his opening lecture he mentioned previous pandemics and said that they could be cyclical in nature, with major ones happening approximately every 100 years. And since the last one was the Spanish flu in 1918 we were overdue another. Those words stuck with me and I had reason to think of them again whenever we were threatened with H1N1, Ebola, SARS.… When none of these outbreaks turned into the global pandemics we were expecting I began to get complacent. In January and February when we were hearing about the cases of a novel coronavirus cropping up in China, I remember some of the consultants discussing it and expressing disbelief that people with holidays in May and June were considering cancelling them. Surely it would all be over by then.

And then the St Patrick’s Day parade was cancelled, people were being asked to work from home, and our changeover was cancelled. It seemed as though overnight we went from thinking that this would be just another scare to changing how the hospital operated. All leave was cancelled. Scrubs became mandatory and any non-essential clinical work was cancelled. The hierarchy changed. Before surgical teams had the longest hours, now infectious diseases and respiratory called the shots. Seven-day weeks became the norm for any team treating Covid-19 patients. Wards closed as the public stayed away from the hospital, and elective procedures were shifted to the private hospital. Surgical nurses now became Covid-19 nurses, and entire teams were being isolated because of false negatives.

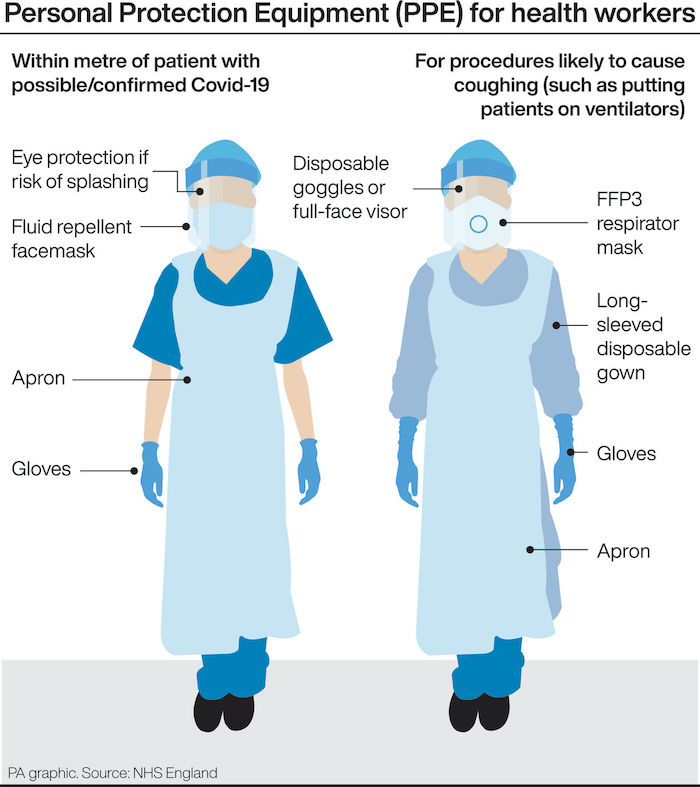

As this was a novel virus, the precautions that staff were told to undertake changed weekly. In the beginning, it was business as usual. But as more and more staff members became ill, social distancing became enforced. Multidisciplinary team meetings became smaller as only essential staff were allowed. In the beginning, the advice was that masks would not protect staff from getting the virus and that in the interest of patient dignity we could not discriminate against those who were Covid-19 negative by wearing a mask or gown. Cases spiked and patients who were initially negative started testing positive. It would be easy to blame someone for this, but in reality the hospital was following the guidelines set out by the WHO, who in turn were trying to advise on a virus of which they had little knowledge. Diagnosis of coronavirus was based on clinical suspicion, radiological findings as well as swabbing, all tempered with the basic commandment of medicine “First do no harm”. We had to balance comprehensive testing with prevention of unnecessary procedures.

Life was strange. Roads were empty and I could nip into work in a fraction of the time. In work I was constantly under pressure, at home there was nowhere to go and no-one to see. Patient contact had always been my favourite and most frustrating part of my job. Now that was severely curtailed. I would spend most of my day donning and doffing PPE, running into rooms of 6 and doing flying ward rounds. The days where a team of doctors greeted you were gone. We became proficient multitaskers, ensuring that any and all jobs were done at the same time to prevent PPE waste. Guidelines specified 15 minutes or less in the room, which was often impossible.

Patients suffered. Not through a lack of care but a lack of socialisation. Visitors were forbidden except under the most limited of circumstances. It is difficult to show compassion and care when a mask and visor obscures your face, when gloves and gowns limit contact. How can a patient be reassured when they can’t even make out the features of those that are caring for them? There were many patients who asked me when I came to review them if I could stay for a chat. It was horrible having to apologise and promise to try and get back to them, knowing that the chances of that were slim.

It’s now a year since I first proudly pinned my intern ID badge on. Lockdown has eased, with social distancing and masks now our main weapons in the fight against the virus. Hospitals are slowly returning to a state of near normality although in many instances the old ways of doing things are finished forever. I’m now starting my paediatric training scheme as an SHO in another hospital after being lucky enough to have spent a month in SBI frantically trying to squeeze in as much research as possible. This would not have been possible without the sacrifices, both within the hospital and with the wider community, as well efforts by SBI management, lab staff and the Bond research group to help me get set up in the lab. While it wasn’t quite the end to my intern year that I had anticipated, I feel fortunate to have been able to be a frontline worker and hopefully my time at SBI is just beginning.