Conflict Photography & Northern Ireland

By Justin Carville

On 30th January 1972, the British Army opened fire on a civil-rights demonstration in the nationalist Bogside area of the city of Derry. Organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, the march, intended to enter the walled confines of the city centre, was halted by Army barricades and diverted to Free Derry Corner on Rossville Street for a rally. Before the rally could start, the British Army launched an attack on the demonstrators firing over 100 rounds into the crowd, shooting dead thirteen nationalists and wounding fifteen others, one of whom died several months later. All were unarmed civilians.

Fulvio Grimaldi- Father Daly waves a white handkerchief as he leads a group carrying the dying Jackie Duddy

The events of this day, the most visual and visualized episode of human rights abuse by the British authorities up to that date, were photographed, filmed and audio-recorded to be broadcast and published by the international media across the world. Despite the voluminous amounts of imagery, both still and moving, taken by local and international media and the British military, however, the exact circumstances surrounding the deaths of fourteen demonstrators have remained disputed for over thirty years, resulting in two public inquiries, the latest of which has yet to publish its findings. The image, still and moving, has remained embedded within these disputes surrounding the events of Bloody Sunday through both its visible depiction of state sanctioned violence and its visible absences in the form of the destruction of photographs taken by military photographers. The photojournalistic image in particular has come to function as a crucial site of contestation, serving to perform as the object and motivation of eyewitness testimony, and the formation of collective cultural memory of Bloody Sunday itself, as well as the broader history of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland.

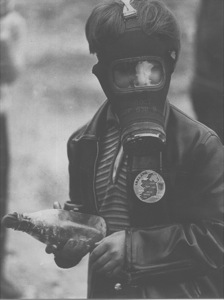

Clive Limpkin- Young boy in a gas mask

The photojournalistic image has continued to serve the visual needs and desires of the public far beyond its intended use to graphically portray the events of Bloody Sunday through the rapid circulation and distribution of the global print media. Clive Limpkin’s 1969 photograph of a nationalist youth wearing a WWII gas-mask during two days of clashes with the RUC after demonstrations against loyalist marchers, known popularly as The Battle of the Bogside, has circulated as both photo-reportage and as an after-image of the city’s past of collective oppression and resistance. Originally published on the cover of a magazine and later Limpkin’s published photo-reportage, Battle of the Bogside, which received the Overseas Press Club of America’s Robert Capa Gold Medal for best photographic reporting in 1972, the photograph flowed through the global print media. Twenty-five years later in 1994, it formed the basis of a commemorative painted wall mural by the Bogside Artists Collective on the gable end of a house in the shadow of Free Derry Corner.

The media philosopher Vilém Flusser has observed that society has become so habituated to the ever-changing photographic universe that they occupy, that it no longer takes notice of the majority of photographs that continuously enter the photoscape of everyday life. The permanently changing photographic universe “where one redundant photograph displaces another redundant photograph” has become familiar, ‘run-of-the-mill’ to the extent that change, ‘progress’, has become un-informative. (Flusser, 2000: 65) What would be truly shocking, Flusser argues, is a stand-still situation, a society were the same photographs would be experienced day after day. Incorporating the monochromicity of photojournalism into the painted wall mural, the rapid displacement of photographs, the function of the apparatus of global media, have been interrupted. Change has been brought to a standstill so that what was intended as the photographic documentation of the contemporaneous event has been transformed into commemorative visualization of the past event within the very place it depicts. Fulvio Grimaldi’s iconic image of Bloody Sunday representing Father Edward Daly waving a white handkerchief as he leads a group carrying the dying body of Jackie Duddy, an image submitted with Grimaldi’s own testimony to the Saville Inquiry, has similarly been transformed through the commemorative practice of wall murals countering dominant narratives of Bloody Sunday and the ‘Troubles’. The photojournalistic image continues to hover over the space of its production not simply as a remediated shadowy simulacra of itself but as the visible material of the past “that weaves memory into the scene of everyday life” (Dawson, 2005: 165). The photojournalistic image thus continues to operate beyond the scope of its intention, serving within the judicial context of eye-witness testimony and the socio-cultural practices of memory production that seeks to contest official histories of conflict.

Bogside Artists Collective murals- Free Derry Corner

Bogside Artists Collective murals- Free Derry Corner

The tensions that exist within photojournalism’s representation of conflict in Northern Ireland have also been incorporated into photographic practices that seek to contest both the content and the ideological apparatus of the international media. Throughout the 1970s in particular, the print media relied on a strategy of portraying the conflict in media res, adopting a visual ideology that sympathised with the fate of the British combat soldier. Editorially much international photojournalism visualized the ‘official perspective’ that suited both the media and the state. (Taylor, 1991: 12) The photographic frame was used to contain the scene, isolating it from what came before and dislocating it from the cultural and political history behind the conflict.

Photographers such as Paul Seawright, Anthony Haughey, John Duncan and Victor Sloan have, through various strategies, incorporated codes and conventions of photojournalistic practice and media representations into their work while simultaneously re-negotiating them to alter and shape the photography’s role in the formation of cultural consciousness of the ‘Troubles’. Aware of photojournalism’s framing and ‘capturing’ of the act of violence as its main visual trope, and its reliance on its ability to organise the unruly into the pictorial space of the single photograph to convey its immediacy, these photographers turned instead to the traces or aftermath of conflict, or used metaphor and allegory to bring more visual depth to the representation of conflict. For these photographers conflict is represented through what has been identified in recent discussions of contemporary photographic practice as ‘late’ or ‘cool’ photography as opposed to the ‘hot’ photographic representation of events as they happen. (Campany, 2003: 124)

Anthony Haughey- British Army Fortifications

This case study explores the tensions both within photojournalism’s representation of conflict in Northern Ireland and between its uses and incorporation into judicial practices of testimony, public practices of memory production and photographic practices that re-negotiate photography’s role in portraying conflict. Within the broader scope of the project it seeks to explore the conventions and ideological characteristics of photojournalism’s representation of conflict in Northern Ireland. In conjunction with this, it will examine the significance of editorial policy and state propaganda in the use of photojournalism to document conflict nationally and globally. Equally it will be concerned with the media industries’ dissemination of representations of Northern Ireland and how this is manifest in local and global contexts. Within the specific context of Northern Ireland, the role of photojournalism in the advocacy of human rights will be explored with specific reference to Bloody Sunday. In particular the continued presence and circulation of photojournalistic images used in publications and remediated public spaces of commemoration will be examined. Additionally the circulation of photojournalistic images between and within official mechanisms of judicial inquiry and spaces of collective memory will be explored to identify how photographic imagery could be used to ameliorate suffering in post-conflict societies.

1997300.jpg)

Paul Seawright- Untitled (Flag) 1997

Click here for ‘Conflict Photography & Northern Ireland’ Bibliography section.

Click here for ‘Conflict Photography & Northern Ireland’ Links section.

Further Resources

- Link 1 to somewhere